MEDICAL EDUCATION: WHERE WE HAVE BEEN, WHERE WE ARE NOW, AND WHERE WE ARE GOING

Introduction

Introduction

- The Student

- The Faculty

- Health Care Reform and the Future

Introduction

Thank you, Henry, for that warm and very gracious introduction. It is a great honor to be the Third Ralph H. and Ruth F. Gross Lecturer, and I thank all of you for attending. Considering how much most of you have listened to me talk over the last 14 plus years, I'm surprised and flattered by the attendance.

I would be remiss if I didn't tell you how the Gross Medical Library Endowment and this lectureship came about -

One evening, Ruth, Bea Dossick and I met for dinner and discussed Ruth's husband, Ralph's intense interest in medicine. Ruth wanted to honor his memory and recognize his interests in an appropriate way. Mr. Gross' concerns about health issues were multifaceted but focused in the area of nutrition. He was a true scholar and depended on medical libraries to do his own research. He used the Calder extensively and frequently consulted with our medical school faculty.

After careful consideration, Ruth and their daughters decided to support the Library rather than establishing a more traditional chair in nutrition. We are deeply grateful and could not agree more with their decision.

A bit more history - the first lecturer was Dr. Manny Papper who gave a scholarly presentation on modern anesthesia and its beginning illustrated by the Romantic poets' concern for the individual. Manny had a tremendous advantage - that was also his Ph.D. dissertation.

Henry King Stanford, the second lecturer, simply relied on his extraordinary memory and entertained us with reflections spanning 50 years. Ruth told me recently just how much she enjoyed that journey down memory lane.

Henry (Mr. Lemkau) asked me to give a scholarly presentation on academia, then and now. Unfortunately, I'm not in a class with Manny Papper as a scholar nor come close to having Henry King Stanford's memory, so I've decided to talk about two things that have allowed our very young school (43 years) to mature beyond its years and become something very special. I'm talking about the students and faculty. They are the driving force in the evolution of a medical center and its commitment to caring about the community it serves.

The official title of this lecture is "Medical Education: Where We Have Been, Where We Are Now, And Where We Are Going." I've decided to change it to the "Then and Now of Students and Faculty" - concentrating on some of the critical issues facing them and academic medicine.

The constant is that the medical students have always been deeply committed and extremely bright individuals. They are a joy to be around and we are privileged (make that blessed) to have the opportunity to train them. The major differences between students then and now are primarily the diversity of their backgrounds, their sophistication and their sensitivity to public need.

Over 50% of the entering class are women. The school has rich representation of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. We have become a leader in attracting African Americans and obviously are well-represented by Hispanic students. None of this characterized the past enrollment. I am very proud of the change and believe such diversity is critical to our profession and for society.

Students are substantially more sophisticated than years ago. Despite the fact that today's practicing physicians complain about HMOs, economists predict that our profession's income will fall (and they are) and that there will be fewer jobs, and some physicians are even going so far (believe it or not) as forbidding their children to enter the field, American college students are stampeding the front doors to medical schools in record numbers.

We have always attracted young people with a desire to help others. However, that altruism was paved with the promise of being their own boss and making big money, especially in the specialties.

Medicine's next generation is choosing the profession with open eyes - expecting to be part of a cost-conscious system oriented toward primary care. Many - maybe most - students know they will work for salary and they are already turning in growing numbers into general medicine.

I'm not certain when students began to be so aware of public problems, but I'm constantly amazed with their involvement in community service. I perused our School's yearbooks dating back to 1956 and began to see evidence of their involvement in the late 60s. That coincides with the times and probably was a reflection of general involvement of students nationwide. I recall students petitioning me to work in Lynn Carmichael's Family Medicine clinics and their establishing their own clinics in the Grove. Whatever its roots, it's great, and I've always been proud that our School not only helped them with their community service projects, but encouraged them, learned from them, and supported them.

With this as a brief overview on students as a background, I'm going to use a few slides outlining the major issues facing students and medical educators. They are taken from a recent report by Dr. Jordan Cohen, President of the Association of American Medical Colleges, who sent me the hard copy of the slides he used in a talk to the Deans at a recent regional meeting.

I do not anticipate any problems in continuing to attract superb young women and men in large number. The class will be made up of students from diverse backgrounds, responsive to community needs. Although students will come prepared to go into primary care fields, better career counseling will be both critical and challenging, especially for medical centers such as ours. The very nature of the UM/JMH Medical Center is a magnet to students to seek specialty training. Everything that happens in Jackson Memorial Hospital is dramatic, and it is not surprising that young people identify with the extraordinary health professionals in the trauma, spinal cord, burn, neonatal, transplantation centers, etc. It's hard to come away from interactions with faculty in the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and not want to be an ophthalmologist. You walk by Jerry Goodwin or Tom Balkany and you want to go into ENT. However, the realities of decreased graduate training slots will force the issue and we will respond. Even more importantly, the realities of the market place will force students to select non-specialty training.

Another major challenge will be to use computer technology to the students' advantage and not permit them to learn medicine at home. Medical education requires role models; it cannot be self-learned. Students must learn to solve problems. No matter how good the computer, it's still a source of information. It can never replace a great teacher during the pre-clinical years or on the wards. The computer cannot examine the patient or make the critical judgment required in patient care. Most importantly, it cannot teach the art of medicine. Fortunately, we have superb teachers and role models. I'm confident that the type of students we're so lucky to teach will continue to realize that you can only learn the profession in the clinical environment and they have the best one in which to learn their chosen profession. We can guarantee their presence by an even greater commitment to excellence in teaching - not easy with the increasing demands on our time.

Changing graduate medical education will be even more challenging. We cannot escape the fact that we are a tertiary medical center. The demands for services will not go down. Mandates to training quotas of primary care physicians will not be easy on us. We cannot simply and arbitrarily decide to train one-half specialists and one-half generalists. The Medical Center service loads, something we have virtually no control over, will facilitate our manpower needs.

The second part of the people equation - the Faculty

We have always been blessed with extraordinary faculty. Years ago, it was a small faculty, very committed to establishing a high quality medical education program and doing their own research. For a young school, we were able to recruit superstars -- scholars and leaders not only willing to take risks in a new and challenging environment, but committed to developing the type of research and educational programs necessary to becoming an excellent medical school.

Over the past 25 years, the two traditional missions (education and research) have been joined by clinical and community services, both of which we are as good at as anyone. During the same period, Federal support for medical education has evaporated, competition for research dollars has escalated, and medical schools have been dependent on the revenues produced by their clinical practices and hospitals. Today, nearly two/thirds of a 450 million dollar budget is derived from our clinical activities.

Unfortunately, this means that faculty are frequently torn by their responsibilities. They are on our faculty because they want to teach and do research. However, in order to support themselves, they must practice in a highly competitive market place. Their clinical demands have grown significantly, forcing them to make tough choices, and have placed today's medical school faculties under unprecedented stress. Our cultural norms have come unglued.

Health Care Reform and the Future

All of this is now compounded by the issues created by managed care and the revolution in health care reform. When President Clinton was elected in '92, we knew there would be change. A year ago, when the Republicans took over the House and Senate, they announced their contract to wipe out the budget deficit by early in the next century. Central to their initiative is significant changes in Medicare, Medicaid and welfare. The rapidity of these changes is escalating even if the President vetoes the budget that will come from Congress in the next two weeks. There will continue to be massive reduction in the growth of the health care industry and managed care will be promoted. We are already a victim of capitation and are assuming risk. The net effect is that the clinical income on which we have become so dependent has leveled and will predictably go down.

Despite these incredible challenges, I am extremely confident that academic medicine will emerge from the current uncertainties as an even more effective instrument for several reasons:

- Our nation's medical schools' ingenuity have placed the United States at the forefront in medical education, research and health care.

- Care of the sickest, most unusual, most vulnerable patients has been at the core of accomplishments and this distinguishes us from all others - it is also appreciated.

- We have consistently been the only part of the health care industry that has committed itself to a societal mission.

These characteristics are the reason that the National Institutes of Health budget has not been cut and may increase modestly. They are the reason that Congress still wants to establish a graduate medical education trust fund and maintain some form of disproportionate share of funding for the poor. Our political leaders are not knowledgeable enough but they continue to recognize our uniqueness. We must make our case over and over again.

We cannot change our commitment to the fundamental missions of education, discovery and health care. However, it will not be business as usual in carrying out our traditional mission. We will have to significantly change organizational structures, programs and activities. Adaptation will be the order of the day and because we have extraordinary faculty and students, we will not only meet the challenge, we will continue to be leaders.

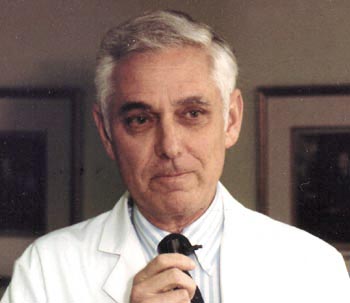

Bernard J. Fogel, M.D., Senior Vice

President for Medical Affairs and

Dean Emeritus, University of Miami

School of Medicine

November 1, 1995

©2002-2017 University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine. All Rights Reserved.